Even if you don’t know anyone who has schizophrenia, chances are you’re familiar with the symptoms.

People with the condition may experience hallucinations, delusions and paranoia, as well as have difficulty concentrating, organizing their thoughts and doing basic tasks of everyday life.

For many years, doctors had little insight into the illness beyond patients’ self-reported symptoms. The causes of schizophrenia, and the way it impacts the brain, were mostly a mystery due to the unique challenges researchers faced in trying to understand the most complex—and least accessible—organ in the body.

But today, with the aid of new technology, that mystery is starting to unravel.

“We’ve seen tremendous advances in the understanding and management of schizophrenia over the past several years,” says Husseini Manji, M.D. Global Therapeutic Head, Neuroscience at Janssen. “It’s a very exciting time in the field.”

The potential to provide new therapies to those affected by schizophrenia is partly what drew Dr. Manji to the company back in 2008, when he was the director of the National Institute of Mental Health Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program.

“Several pharmaceutical companies had tried to convince me to join them, but Johnson & Johnson was committed to neuroscience at a time when many of them were pulling away from it," he explains. "The science of mental illnesses had matured to the point that it could be converted to advances in treatments for conditions like schizophrenia.”

For the 1 percent of the U.S. adult population that has schizophrenia—that's almost 2.5 million people—advancements in the understanding and treatment of such a complicated illness can’t come soon enough.

Husseini Manji, M.D.

Global Therapeutic Head for Neuroscience at Janssen

Schizophrenia is one of the most debilitating mental illnesses, typically emerging in a person’s late teens or early 20s. The consequences can be devastating: Those with schizophrenia are at greater risk of unemployment, homelessness and incarceration. Approximately one-third will attempt suicide, and about one in 10 will eventually take their own lives.

Although researchers know that schizophrenia is largely a genetic disorder, less is understood about the biological underpinnings of the disease. But thanks to advances in brain imaging, scientists like Dr. Manji are beginning to get a clearer picture of the changes the brain undergoes in someone with schizophrenia—changes that appear to occur even before clinical symptoms emerge.

Studying the Brain of Someone with Schizophrenia

Over the past decade, several brain-imaging studies have shown evidence of structural abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia, providing researchers with clues to the root biological causes of the disease and how it progresses.

One 15-year study, partly funded by Janssen and published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, revealed that patients at the first episode of psychosis had less brain tissue than healthy individuals. Although the loss appeared to plateau over time, long relapses of psychosis were associated with additional shrinkage.

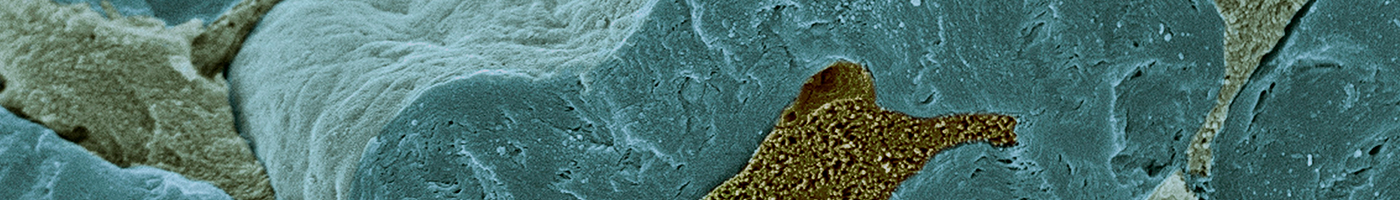

“We knew from earlier post-mortem studies of the brains of people with schizophrenia that they have fewer synapses and neuron branches, which allow neurons to communicate,” explains Scott W. Woods, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and the director of the PRIME Psychosis Prodrome Research Clinic at Yale University. “So, we believe that this is what accounts for the shrinkage of brain tissue we’re seeing in scans.”

While everyone undergoes a normal loss of some gray matter—which contains neurons and their short branches—during adolescence, experts theorize that the process may become too fast or aggressive in some people at high risk of schizophrenia, triggering psychosis.

Imaging studies reveal a lack of both gray and white matter in the brains of people who have schizophrenia. While everyone undergoes a normal loss of some gray matter—which contains neurons and their short branches—during adolescence, experts theorize that the process may become too fast or aggressive in some people at high risk of schizophrenia, triggering psychosis.

The abnormal development of white matter, which contains the long-range, myelin-coated nerve fibers that connect the four lobes of the brain, may also be a tipping point for some individuals predisposed to the condition. A study published in NeuroImage: Clinical suggests this may be associated with the cognitive symptoms people with schizophrenia experience, such as learning and memory dysfunction, as well as apathy and low motivation.

What causes these losses is still unknown, but the prevailing theory points to inflammation, a contributing factor to the progression of many diseases. Two years ago, British researchers discovered increased immune cell activity in the brains of people with schizophrenia and those at risk for the disease. It’s unclear what might stimulate the inflammatory process, but earlier studies have shown a link between infections early in life and the incidence of schizophrenia.

“Inflammation is one of the mechanisms that removes synapses and neuron branches in the brain, so if it was present in an excessive degree, that could account for the loss,” Dr. Woods explains.

Cutting-Edge Ways to Help Protect the Brain

To scientists at Janssen, these brain abnormalities underscore the importance of treating people in the earliest stage of schizophrenia, and identifying new ways to minimize the damage caused by multiple relapses.

One significant area of research at Janssen is devoted to improving medication adherence. It’s an issue for every doctor who treats chronic conditions, but it’s particularly challenging for those who work with patients who have schizophrenia. Only about 50 percent of patients take their medication as directed, which creates a cycle of relapse and symptom recovery that’s difficult to break—and can reduce response to treatment.

“Unfortunately, the nature of schizophrenia limits people’s insight into their illness,” Dr. Manji says. “As patients start to feel better, they often discontinue their medication. But unlike in people who have diabetes, for example, who will feel the ramifications of missing a dose of insulin just hours later, patients with schizophrenia who stop taking antipsychotic medication might not experience signs that they’re relapsing for weeks.”

To that point, scientists at Janssen have been focused on helping address this problematic cycle of relapse through the development of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications that patients take less frequently than other treatments.

To further help shield patients from the damaging effects of multiple relapses, scientists at Janssen are also investigating ways to identify those at high risk for relapse using data collected via smartphones, health trackers and on-body sensors.

Long-acting injectable medications are administered by healthcare providers, so if a patient misses a dose, the treatment team is aware and can intervene.

To further help shield patients from the damaging effects of multiple relapses, scientists at Janssen are also investigating ways to identify those at high risk for relapse using data collected via smartphones, health trackers and on-body sensors.

“We want to know whether tracking factors such as sleep, activity level, engagement with others and other biomarkers could provide doctors with early warning signals that someone is about to relapse,” Dr. Manji explains. “This information could give doctors the opportunity to identify and reach out to those patients who are starting to do poorly, instead of waiting for them to come in for their scheduled appointments.”

Including health technology in a patient’s treatment plan could also provide doctors with more objective information about how the person is really faring. Data shows that when patients are asked how they’ve felt during the past few weeks, their memory is primarily focused on yesterday or the day before. But with more long-term, measurable data in front of them, doctors can not only get a clearer idea of how a patient is doing, but they can also use their time with the person more constructively.

“If patients are stable and you don’t have to spend as much time simply addressing psychotic symptoms, you can then focus on constructive ways to help give them their lives back,” Dr. Manji says.

Treating the Whole Patient, Not Just the Symptoms

To truly improve the lives of those with schizophrenia, researchers are committed not just to developing novel medications but also to advancing integrative care. Dr. Manji says that working at Johnson & Johnson appealed to him because the company shared his belief that medicine needed to move beyond pills to give those with schizophrenia the best possible outcome.

“We want people to understand that approaching schizophrenia from a more holistic, integrated model of care is undoubtedly the best way forward,” he says. “Mental illness has a major impact on every aspect of a person’s life—their physical health, behavior and relationships. Patients will require several types of interventions, not just medication.”

At Janssen, one area of investigation is the vital role caregivers play—and the challenges they face—in the treatment and management of those with schizophrenia. Currently, patient recruitment is underway for a year-long Family Intervention in Recent Onset Schizophrenia Treatment (FIRST) clinical trial. Researchers plan to evaluate the overall effect caregivers can have on those under their care when they participate in a study-provided caregiver psycho-education and skills training program. The hope is that this type of program can help reduce the number of treatment failures, such as psychiatric hospitalization and suicide or suicide attempts.

The company’s deep commitment to improving patients’ lives is also reflected in its collaborative initiatives with academia, the government and the biotech industry. “This illness is so complex that we have to work together to advance research,” Dr. Manji says.

In 2015, Janssen Research & Development launched the Open Translational Science in Schizophrenia (OPTICS) Project, a forum for collaborative analysis of Janssen’s clinical trial data and publicly available schizophrenia data from the National Institutes of Health.

The company is also an industry partner in a recently created consortium led by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies designed to improve the quality of induced pluripotent stem cell technology, a tool that enables scientists to collect skin cells from patients with mental disorders and convert them to neurons. By creating a neuronal model of schizophrenia using patient-derived cells, researchers hope to gain new insight into the underlying mechanisms of the disorder in order to develop more targeted treatments.

Dr. Manji believes that this type of innovative work will lead not only to new treatments for schizophrenia but also methods for delaying and potentially even preventing it.

“We now know that schizophrenia, like many diseases, doesn’t strike people overnight,” he explains. “The illness is brewing before someone enters full-blown psychosis, and the sooner treatment starts, the better the person’s long-term prognosis is.

If we can identify people who are at high risk of developing schizophrenia, and learn what’s happening to them at the earliest stages, we could potentially change the entire trajectory of the disease.”

This article, written by Jessica Brown, first appeared on www.jnj.com in May 2017